Protecting House and Home: Louisiana’s Number-One Key to Resilience

July 18, 2021

LSU researchers, from coastal scientists and engineers to sociologists and psychologists, are working to protect Louisiana residents and homeowners from the potentially devastating impacts of flooding. From economics to equity to emotion and psychological well-being, there are solutions to living in a flood-prone state.

Add a caption to your photo.

– ‘How can we make progress toward resilient communities and economies if mathematics tells us that half of the homes located in the floodplain will flood at least once?’ asks the LSU-UNO Flood Safe Home website.

Louisiana homeowners who see their house flood, and maybe not for the first time, face difficult decisions. Rebuild, sell, and move? Rebuild and stay? Can you even afford to rebuild? And if you do, should you invest more money to elevate your home to prevent it from flooding again?

Unfortunately, there is little help in making these decisions, while the consequences are far-reaching. Emerging studies and new work by LSU researchers, however, aim to give residents better guidance so they can optimize the outcomes for themselves, their families, and their communities. LSU scholars in construction management, oceanography and coastal sciences, sociology, and psychology are working to gather data on the economic, equity, and emotional aspects of living in what appears to be an increasingly flood-prone place. And not just in coastal Louisiana, but across the state, including the Red River, Ouachita River, Calcasieu River, and Mississippi River watersheds, to the borders of Texas, Arkansas, and Mississippi.

While flooding is a concern for a majority of the state’s residents—including many who live outside the FEMA-designated 100-year flood zones, where flood insurance is required for a mortgage—the risks and impacts are not the same for everyone.

Ironically, the most flood-prone areas are often the most populous. Living near water adds to one’s quality of life, and water is a key conduit for industry, transportation, tourism, and recreation. There is also place attachment, sometimes built over generations, where memory and feelings of home—even who you are as a person or family—is tied to the land. This can make seemingly poor decisions, such as staying in a flood-prone place, more understandable. But as the land erodes and subsides (sinks), sea levels rise, and storms get stronger and more persistent—with more rainfall—this means more risk for more people. The Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority, or CPRA, estimates the cost of flooding (now the most common type of disaster in the U.S.) to go from about $3 billion per year today to around $20 billion in 50 years in Louisiana, if we take no further action to increase flood protection. If the population stays the same and those costs are spread evenly among all people in the state, we’re looking at $4,000 per person per year, or an average of $11,000 per household. But while flooding is a concern for a majority of the state’s residents—including many who live outside the FEMA-designated 100-year flood zones, where flood insurance is required for a mortgage—the risks and impacts are not the same for everyone, say Carol Friedland, associate professor of construction management; Robert Rohli, professor of oceanography and coastal sciences; Kevin Smiley, assistant professor of sociology; and Katie Cherry, professor of psychology at LSU.

“When you go buy a dishwasher, it has an Energy Star rating on it that says, ‘you

can expect to pay $58 per year in electricity for this dishwasher,’ but there’s nothing

like that for homes,” Friedland said. “That’s something we’re working to change, and

our idea is that people understand dollars and will make better decisions if they

have accurate and personalized information on what living in this or that home is

really going to cost them.”

Read more about how LSU researchers are working to increase disaster resilience in

Louisiana by protecting the most valuable thing most of us will ever own—our homes.

Economics

FEMA’s flood zone map is based on the 100-year floodplain, which includes areas (in dark blue) with a one-percent chance of being inundated in any given year. Homes in these areas have at least a 50/50 chance of flooding in 70 years.

– Map courtesy of Jacob Mullins

Carol Friedland, LSU associate professor of construction management, has a simple motto.

“If you build your house higher, it won’t flood as much,” she said. “That essentially summarizes what I do.”

But the apparent simplicity of that statement comes up against layers upon layers of complexity when it comes to building codes, elevation and flood data, home values, and residents’ understanding of risk. For one, Louisiana’s statewide building code does not include the concept of freeboard—the distance between base flood elevation (how high the water is expected to rise in a 100-year flood) and the first-floor elevation of a house. There is currently no statewide freeboard requirement for construction. Friedland is now collaborating with other researchers at LSU and University of New Orleans (UNO) to help Louisiana builders, homeowners, and community officials better understand freeboard, and how it could make economic sense—at least in the long run. Another important aspect is that the price of a home that’s been elevated is often the same as a similar-sized house that hasn’t been elevated—home appraisals generally don’t take flood safety into account. Price then begins to separate from actual value over time, making it more difficult to understand exactly what you’re buying. Also, since most people don’t build their own house, but buy it from someone else, they don’t get much say as far as its initial elevation, or price.

Elevating an existing home can be a significant investment. On average, it costs $180,000. Elevating a house in the construction phase is at least 10 times more affordable, but any additional cost to a developer or builder that doesn’t lead to a higher selling price isn’t likely to be deemed ‘good business.’ Friedland and her team, including LSU oceanography and coastal studies professor Robert Rohli, are working to change that.

Home appraisals generally don’t take flood safety into account. Price then begins to separate from actual value over time.

“If the economics worked out, everybody would want to elevate,” Friedland said. “But we need to incentivize the builders and developers, and the only way to do that is to make sure they get paid for hazard-resistant features. We are working toward a new appraisal addendum for home resilience. The Appraisal Institute already has one for green and energy efficient features, such as solar panels. So, why not have one for flood-safe homes?”

Friedland thinks of homes as residents’ first line of defense in a disaster. As long as most people can manage to stay in their homes, and not have to relocate for months, as hundreds of thousands of New Orleans-area residents had to do for Hurricane Katrina, gutting the city, communities could rebuild faster. Life could go on.

“If you want to know what resilience really means, that’s it,” Friedland said. “For most of us, our home is our number-one key to resilience.”

To help Louisiana homeowners and homebuyers become more resilient, and with support from Louisiana Sea Grant, Friedland and her team are building a website. Yongcheol Lee, assistant professor of construction management at LSU, leads the web development, and postdoctoral research associate Arash Taghinezhad (construction management) collaborates with four LSU doctoral students: Rubayet bin Mostafiz (oceanography and coastal sciences), Ehab Gnan (engineering science), Shifat Mithila (computer science/engineering), and Jiyoung Lee (geography and anthropology).

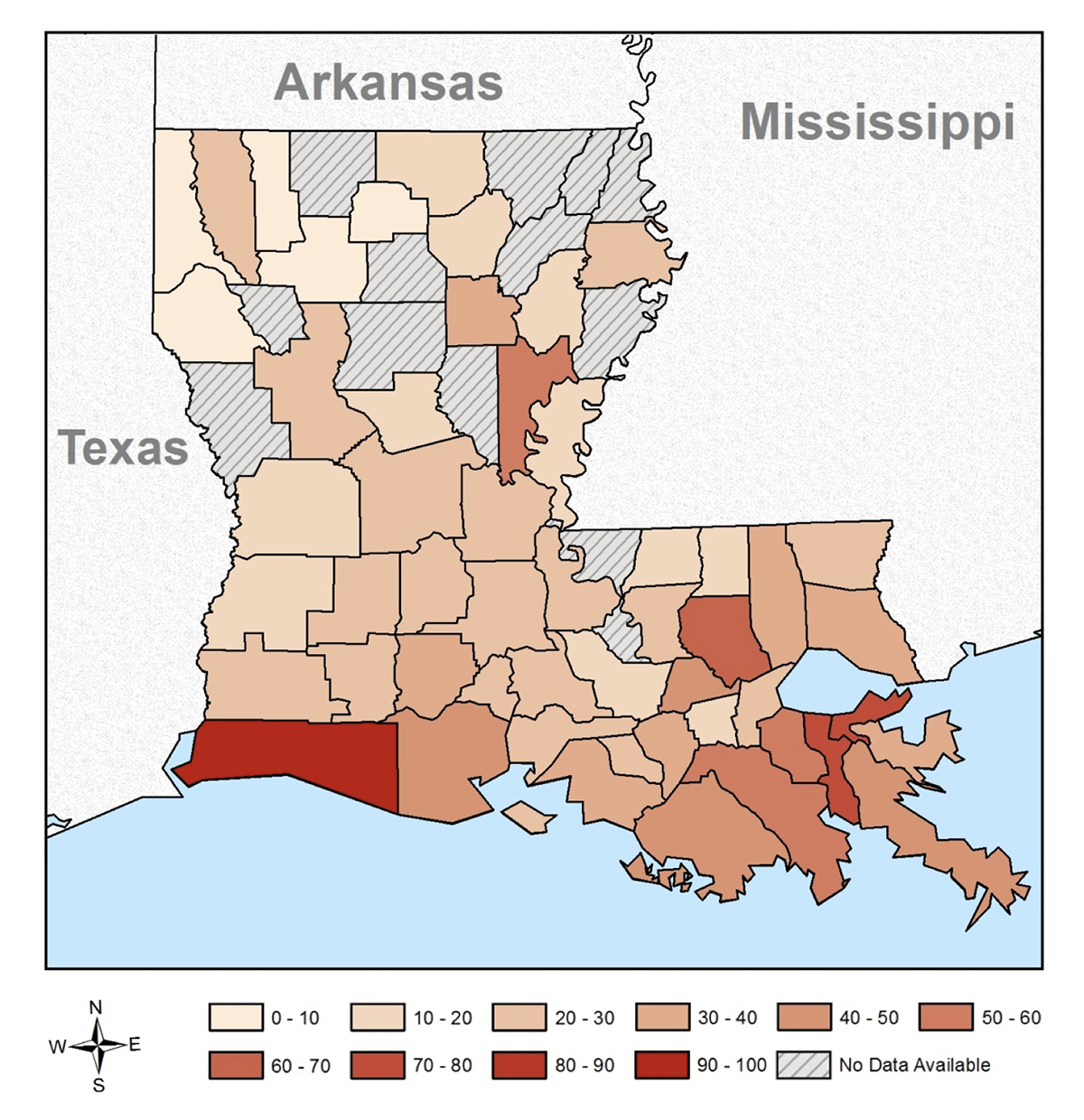

Percentage of parish population who lives in the floodzone, according to FEMA's Flood Insurance Rate Map. Flooding risk is often compounded as more people tend to live near water.

– Map courtesy of the Governor’s Office of Homeland Security & Emergency Preparedness (GOHSEP)

While the overarching project is much larger, the website, Flood Safe Home, will be its public face and how most users will be able to access the research. Building on the best available flood depth data, Friedland’s team is making the information to homeowners more fine-grained, customized, and interactive, so residents also can explore what-if scenarios, such as ‘What if I elevate my home 3 feet or 6 feet—what difference does that make in cost right now and potential savings on flood insurance and repairs in the long run?’ And instead of a risk score, which can be difficult to understand and act on, residents can look at dollars and cents.

“I’m not sure people find it easy to make difficult financial decisions based on risk scores,” Friedland said. “Everyone thinks they’re going to win the lottery, but they don’t think they’re going to flood. And yet, if you live in the 100-year flood zone, you have a 50-50 chance of flooding in 70 years. That’s why it was important to us to translate all of the available information about risk into average annual loss, so you know how flooding and flood mitigation will affect you personally, what you can do to decrease how much you’re really paying over time, and optimize total cost.”

By October, Friedland’s team expects to have Flood Safe Home fully built out for three Louisiana parishes: Jefferson, Terrebonne, and St. Tammany. They hope to soon expand the scope to include 20 coastal parishes, then statewide.

“Maybe the most important part of Flood Safe Home is allowing people to enter their own data, like how far off the ground their house is, or how many stories,” Friedland said. “The data you get from any platform is only as good as the data you put in. If the base data is sourced from a national database that’s maybe not accurate and hasn’t been updated in a while, people lose confidence if the number they get for their own house is the same as for another house they know from experience shouldn’t be the same. Trust is key.”

“Everyone thinks they’re going to win the lottery, but they don’t think they’re going to flood.”

Carol Friedland, LSU associate professor of construction management

Christopher Pulaski is the director of planning and zoning for Terrebonne Parish, located at the bottom of the Mississippi watershed. He supports the LSU-UNO effort.

“As far as flood protection and storm water management, we’ve done it all,” Pulaski said. “Through LSU’s and UNO’s Flood Safe Home program, we can now share our knowledge and experience from decades of hazard mitigation and restoration efforts and get valuable information about new strategies we can use to educate our residents, stakeholders, and public officials to better protect our parish. Education is a key component. People tend to respond negatively to ideas they don’t understand.”

Freeboard has been one of those ideas, he argues, and Pulaski is excited about the new tools Terrebonne Parish will be able to use to “educate our people.”

“Creating flood-safe homes will always come with an up-front cost—there’s no getting around that,” he said. “But if the true value of a flood-safe home could be acknowledged in the appraisal, as this research team suggests, this would benefit both the bank and the buyer. For the homeowner, the cost could be rolled into the mortgage, and everyone would get more protection of their investment.”

“Through LSU’s and UNO’s Flood Safe Home program, we can now share our knowledge and experience from decades of hazard mitigation and restoration efforts and get valuable information about new strategies we can use to educate our residents, stakeholders, and public officials to better protect our parish.”

Christopher Pulaski, director of planning and zoning for Terrebonne Parish

Friedland’s team’s benefit-cost analysis of making freeboard part of the building code takes potential drawbacks into account as well. If a tree falls on your house, causing substantial damage, and your house doesn’t meet the minimum requirement of freeboard, you would have to both repair and elevate your house. That could easily cost more than many homeowners could afford. And as builders held to a higher standard pass on additional construction cost to buyers, home prices will likely go up. This could lock lower-income individuals and families out of the primary vehicle to wealth in the U.S.—homeownership—and worsen the nation’s housing affordability crisis, leading to greater disparities for at-risk communities.

“My counterargument to that is that homeowners actually can pay less money every month and reduce their flood risk, thus reducing overall cost of homeownership and increasing resilience,” Friedland said. “We know floods and other hazards disproportionately affect low-income and vulnerable populations. Floods are devastating when you have your life savings tied up in your home with few additional resources to recover.”

Maggie Talley, director of floodplain management and hazard mitigation in Jefferson Parish where more than half of the population lives in a high-risk flood zone, also supports the project.

“Implementing higher building standards like freeboard is safer for our citizens and our housing stock,” said Talley. “However, there are many barriers to freeboard, and this project will help us better understand those barriers and identify ways to move through them.”

LSU Construction Management Researcher Studies Associated Property Risk

Equity (home equity, but also fairness)

Using Hurricane Harvey as an example for his study, LSU sociologist Kevin Smiley discovered how Black and Latinx communities suffered disproportionately and lost more in the widespread floods that followed, especially outside the FEMA-designated floodplain.

When Hurricane Harvey hit Houston, Texas in 2017, most of the flooding occurred outside of the FEMA-designated floodplain. This meant many homeowners didn’t have flood insurance, and were out of pocket for repairs. And disproportionately many of those homeowners were Black or Latinx, according to new research by LSU sociologist Kevin Smiley.

“Every single American city is to some degree residentially segregated by race and class, and those disparities are often going to map right on top of unequal flood risks as well as impacts,” Smiley said. “For decades, we’ve seen a lot of urban development in or near floodplains, and the realm of risk probably far exceeds the zones designated as risky.”

About one-third of all claims made to FEMA come from outside the 100-year floodplains, and there is little evidence homeowners in those areas buy flood insurance.

“We have this very binary way of looking at flood risk—you’re either in the flood zone and have to buy insurance, or you’re not in the flood zone and don’t have to buy insurance,” Smiley said. “This belies the actual risk. The FEMA flood models are clearly inadequate in identifying flood risk for local communities, especially minority communities and in Black neighborhoods that consistently have higher levels of flooding outside the floodplain.”

Smiley joins LSU professor of construction management Carol Friedland (read more above) in shining new light on hidden risk. FEMA’s flood maps also weren’t designed to account for flooding ‘from above,’ meaning from intense rainfall, but rather ‘from below,’ from rivers and oceans.

“Changing weather patterns and the sheer size of environmental challenges we face here in Louisiana put us on the front line,” Smiley said. “And if we want sustainable communities that can get through a disaster and recover, we have to think about how environmental change relates to equity. The hardest-hit tend to have pre-existing social vulnerabilities, and we have to think about how flooding and natural disasters may in fact be worsening those issues.”

“The FEMA flood models are clearly inadequate in identifying flood risk for local communities, especially minority communities and in Black neighborhoods that consistently have higher levels of flooding outside the floodplain.”

Kevin Smiley, LSU sociologist

Spatial disparities based on race are already apparent in how homes are appraised.

“Two homes with the same square footage and the same-size yard and the same beautiful porch will be appraised differently based on the racial composition of the neighborhood,” Smiley said. “But when it comes time for disaster recovery funds to be dispersed, one house gets more money than the other house even if the repairs cost the same.”

Smiley is working to bridge the research gap in how social inequalities intertwine with flood hazards. While expanding the designated flood zones would allow more at-risk residents to make a rational decision on whether to move, stay, or elevate their home, it’s not an easy fix, Smiley argues. Instead, it comes with its own problems, which could increase spatial, racial, and class disparities.

“When you’re put into the flood zone and have to buy flood insurance to keep your mortgage, that premium can go from zero to something quite high,” Smiley said. “That money might simply not be in your budget. Instead, it could be the college savings you had for your child. And if an area suddenly is deemed at greater risk for flooding, home values could go down. This could wipe out wealth. Moving, also, can have severe consequences. Can you afford to buy wherever you’re going? Loss of community can also have social and financial impacts, including on mental health. Where we live and whether we own our home impacts everything in a person’s life.”

Emotion and Psychological Well-Being

People who experience repeat disaster can be more prone to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), but the lived experience of overcoming past hardships can also be an asset for hurricane and flood survivors, according to recent research by LSU Professor of Psychology Katie Cherry.

– Illustration by Elsa Hahne/LSU

The cost-benefit analysis of elevating homes Friedland and her team are conducting doesn’t consider the emotional toll of severe weather events. For people who are directly affected by floods and hurricanes, there is often a difficult tangle of expenses and real losses to sort through, including potential loss of human life, treasured belongings, or lost productivity or wages due to displacement after a disaster.

“Families who have lost their homes after a flood witness a lifetime built together washed away, now a lifeless debris pile at the end of the driveway,” LSU Professor of Psychology Katie Cherry said. “Such losses can be brutal.”

For the last 16 years, Cherry and her team have been conducting research to shed new light on the psychosocial consequences of hurricanes and flooding to understand how devastating environmental events impact people over their lifespan. Older adults talk about the unnamed storm of 1947 or hurricanes Audrey in 1957 or Betsy in 1965, while most people remember 2005’s Katrina and Rita when millions of U.S. Gulf Coast residents lost their homes and livelihoods. Some permanently relocated to other cities and states while others returned to their flooded homes and communities to rebuild and recover where living with water is a way of life. Then the floods of 2016 became another before-after reference.

Cherry’s research on post-disaster resilience and long-term recovery in Katrina survivors from the New Orleans area has resulted in a wealth of published research over the years. Her preferred methodology is face-to-face interviews.

“Current and former coastal residents have shared their lived experiences with me and my students,” Cherry said. “We’ve spent long afternoons with adults who lost everything they’d acquired in life, and the knowledge they impart is enlightening and immeasurably valuable. Most importantly, it’s a lesson in hope.”

“Disaster survivors ... provide valuable insights on how to manage stressors and how to best prepare for future severe weather events we know are coming.”

Katie Cherry, LSU Professor of Psychology

Some of the interviewees had permanently relocated inland after the 2005 hurricanes before flooding again in 2016.

“Disaster survivors will tell you about grief and great loss, displacement from home and family, and how they created a ‘new normal,’” Cherry said. “They provide valuable insights on how to manage stressors and how to best prepare for future severe weather events we know are coming.”

According to Cherry, disaster survivors can provide an authentic and inspiring model of how to cope and move forward despite uncertainty. Her recent book, The Other Side of Suffering: Finding a Path of Peace after Tragedy (Oxford University Press, 2020) conveys the central message that despite material losses, disaster survivors do gain something of great value: the knowledge and lived experience that there is hope and healing after tragedy.

Denham Springs boat rescue on August 13, 2016.

– Photo courtesy of Katie Cherry

“I spent 10 years writing this book for the research participants we interviewed, so they would be able to have the scholarship that arose from the study in a tangible form they can share with others, grandchildren, and future generations,” Cherry said. “Resilience is dynamic and can mean different things; it can be a property of homes or a property of people, it can be both a predictor and an outcome. Resilient living after a flood means coping with losses and uncertainty in an adaptive way.”

In current research supported by the National Science Foundation, Cherry and her team are studying the combined impact of prior hurricane experience and 2016 flood recovery stressors on cognition, health, and well-being.

“We have included two phases of testing to track how initial responses may change over time,” Cherry said. “Our hope is that this project will provide a wealth of new evidence-based knowledge on the impact of prior catastrophic losses.”

This news story was featured in LSU’s free, quarterly research publication, Working for Louisiana, where you can learn more about how work on every LSU campus impacts residents and industry in the state, and beyond.